We often joke that our attention span has shortened significantly in recent years with the rise of digital technology and screen-centric entertainment, but there is solid science to support this observation. In fact, shorter attention spans are a side effect of the recent explosion of screen distractions, as neurologist and author Richard E. Cytowic argues in his new book, “Your Stone Age Brain in the Screen Age: Coping with Digital Distraction and Sensory Overload” (MIT Press, 2024).

In his book, Cytowic discusses how the human brain has not changed significantly since the Stone Age, leaving us poorly equipped to handle the impact and allure of modern technologies — particularly those promoted by big tech companies. In this excerpt, Cytowic highlights how our brain struggles to keep up with lightning-speed changes in modern technology, culture, and society.

Hans Selye, the Hungarian endocrinologist who developed the concept of stress, said that stress “is not what happens to you, but how you react to it.” The quality that helps us handle stress successfully is resilience. Resilience is a welcome quality because all demands that take you away from homeostasis (the biological tendency in all organisms to maintain a stable internal environment) lead to stress.

Screen distractions are a prime candidate for disturbing homeostatic balance. Long before the advent of the personal computer and the Internet, Alvin Toffler popularized the term “information overload” in his 1970 bestseller, Future Shock.

He eventually promoted the depressing idea of human dependence on technology. By 2011, when most people didn’t have smartphones, Americans took in five times more information in a typical day than they did twenty-five years earlier. And now even today’s digital natives complain about how stressed out their ever-present technology is making them.

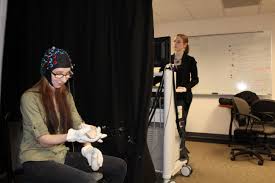

Visual overload is likely to be a greater problem than auditory overload because today, eye-to-brain connections are physically about three times as numerous as ear-to-brain connections. Auditory perception mattered more to our early ancestors, but gradually vision gained prominence. This can bring to mind what-if scenarios.

Vision also prioritized simultaneous input over sequential input, meaning there is always a delay from the time the sound waves hit your eardrums to the time the brain understands what you are hearing. The simultaneous input of vision means it takes only one-tenth of the second to understand what it takes for information to travel from the retina to the primary visual cortex, V1.

Smartphones easily win out over traditional telephones for anatomical, physiological, and evolutionary reasons. The limit to what I call digital screen input is how much information the lens in each eye can transfer to the retina, the lateral geniculate, and then to V1, the primary visual cortex.

The modern dilemma we have gotten ourselves into hinges on flux, the flow of radiant energy bombarding our senses from far and near. For ages, flux was the only thing human sense receptors had to convert sight, sound, and taste from the natural world into perception. From that time to today we have been able to detect only the tiniest fraction of the total electromagnetic radiation that instruments tell us objectively exists.

Cosmic particles, radio waves, and cellphone signals pass us by unnoticed because we don’t have biological sensors to detect them. But we are sensitive, and very sensitive, to a manufactured flux that began in the twentieth century, layered on top of the natural background flux.