Scientists have discovered that when asteroids collide with extremely dense dead stars called neutron stars, mysterious bursts of energy called fast radio bursts (FRBs) can be produced. Such a collision releases enough energy to meet humanity’s power needs for 100 million years!

FRBs are momentary pulses of radio waves that can last from a fraction of a millisecond to a few seconds. In this period, an FRB can release as much energy as it would take the Sun several days to radiate.

The first FRB was observed in 2007, and since then, these bursts of energy have maintained their mystery as they were rarely seen until 2017. That was the year the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment (CHIME) came online and began making frequent FRB searches.

“FRBs defy explanation so much so that there are over 50 possible hypotheses about where they come from – we counted!”

A possible connection between FRBs and asteroids, as well as comets colliding with neutron stars, has been suggested before. This new research by Pham and his colleagues further solidifies that connection.

“It has been known for many years that asteroids and comets can produce FRB-like signals by colliding with neutron stars, but until now it was unclear whether this happens frequently enough in the universe to explain the rate at which we see FRBs,” Pham said. “We have shown that interstellar objects (ISOs), a less studied class of asteroids and comets that are thought to exist between stars in galaxies throughout the universe, may be so frequent that their collision with neutron stars could explain FRBs!”

Pham added that the team’s research also showed that other expected properties of these impacts match observations of FRBs, such as their duration, energy, and their rate of occurrence over the lifetime of the universe.

The question is: Even though asteroid impacts can be devastating (just ask the dinosaurs), how could they possibly release the same amount of energy that a star takes days to radiate?

Extreme stars mean extreme explosions

Neutron stars form when massive stars die and their cores collapse, creating dense bodies with the mass of the sun that are no bigger than an average city on Earth.

The result is stellar remnants with extreme properties, such as the densest matter in the known universe (a teaspoon of one would weigh 10 million tons if brought to Earth) and magnetic fields that are the strongest in the universe, trillions of times stronger than Earth’s magnetosphere.

“Neutron stars are extreme places, with masses greater than the sun’s mass compressed into a sphere about 12 miles (20 km) across, giving them the strongest gravitational and magnetic fields in the universe,” team member and Oxford University astronomer Matthew Hopkins told Space.com. “This means that when an asteroid or comet hits someone, a huge amount of potential energy is released, in the form of a flash of radio waves so bright that it can be seen across the universe.”

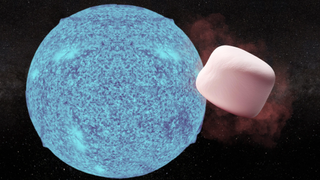

So, how much energy are we talking about here? To consider this, let’s replace asteroid with something much sweeter.

According to NASA’s Goddard Flight Center, if a normal-sized marshmallow is dropped on the surface of a neutron star, the gravitational effect of the dead star is so great that it will fly away at a speed of millions of miles per hour. This means that when the marshmallow hits the neutron star, the collision releases as much energy as a thousand hydrogen bombs exploding simultaneously!

How much energy is released from an asteroid/neutron star collision depends on several factors.

“The energy released depends on the size of the asteroid and the strength of the magnetic field on the neutron star, both of which can vary greatly, by several orders of magnitude,” Hopkins said. “For an asteroid with a diameter of 0.62 miles (1 km) and a neutron star with a surface magnetic field strength one trillion times greater than the strength of Earth’s magnetic field, we calculate the energy released as about 10^29 joules (that is, 10 followed by 28 zeros).

“This is an enormous number, about one hundred million times greater than all the energy used by all of humanity in a year!”

Clearly, asteroids colliding with neutron stars can release enough energy to explain FRBs, but do these collisions occur frequently enough to explain FRB observations?