New observations by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have further cemented one of physics’ most bizarre observations — that the universe expanded at different speeds at different stages of its lifetime.

This puzzle, referred to as the Hubble tension, has fueled a debate among astronomers that could transform or even overturn the field entirely.

In 2019, measurements by the Hubble Space Telescope confirmed that the problem was real. Then in 2023 and 2024, even more precise measurements from the JWST confirmed the discrepancy.

Now, further measurements have used the largest sample of JWST data ever collected in its first two years in space to further cement the problem. The new physics that answers the mystery is still unclear, but as researchers describe in a paper published Dec. 9 in The Astrophysical Journal, the tension isn’t going anywhere.

“The more work we do, the more it becomes clear that the cause is much more interesting than a flaw in the telescope. Rather, it appears to be a feature of the universe,” Adam Riess, a professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University and a Nobel laureate, told Live Science. “The [next] steps are many. More data and new ideas are needed on many fronts.”

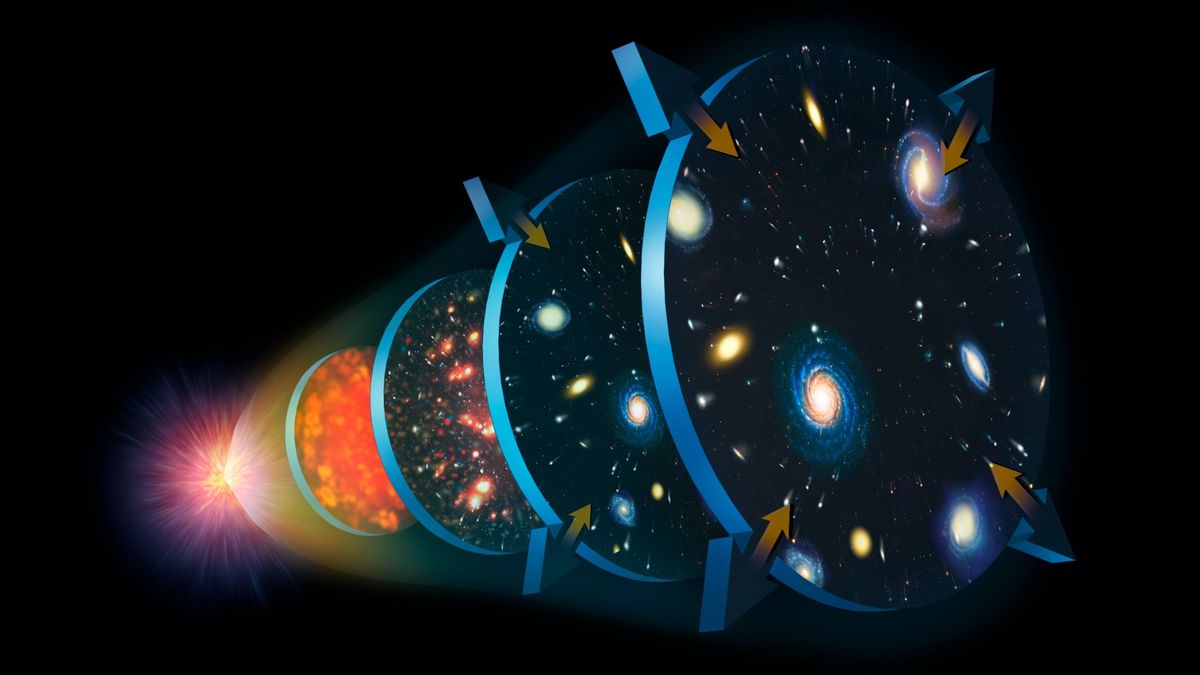

There are two gold-standard methods for figuring out the Hubble constant, the value that measures the speed of the universe’s expansion. The first is derived by measuring tiny fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background — a pristine snapshot of the universe’s first light, just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

After mapping this microwave hiss using the European Space Agency’s Planck satellite, cosmologists estimated the Hubble constant to be about 46,200 miles per million light-years, or about 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/sec/Mpc). This, along with other measurements of the early universe, aligns with theoretical predictions.

The second method operates using pulsating stars at closer distances and in the later life of the universe, called Cepheid variables. Cepheid stars are slowly dying, and their outer layers of helium gas grow and shrink as they absorb and release the star’s radiation, causing them to periodically flicker like a distant signal lamp.

As Cepheids become brighter, they pulsate more slowly, allowing astronomers to measure the stars’ intrinsic brightness. By comparing this brightness to their observed brightness, astronomers can tie Cepheids into the “cosmic distance ladder” to look even deeper into the universe’s past.

With this ladder, and by linking the brightness of Cepheids to explosions from Type Ia supernovae, astronomers can find a precise number for the speed of the universe’s expansion from how the light of the twinkling stars has been stretched, or redshifted. The Hubble constant returned by this method is about 73 km/s/Mpc: this value is far outside the error range of the Planck measurement.

Astronomers have put forward various explanations for the reason for this disagreement, some of which have attempted to highlight the possibility of systematic error in the results. In the meantime, Riess and his team are reinforcing the tension with increasingly precise and comprehensive studies.

This new study is another link in this chain. Covering about a third of the sample size of the 2019 Hubble study, the new analysis used the JWST to measure the sample’s Cepheid distances to within 2% accuracy – a huge improvement on Hubble’s accuracy of 8-9%.

Cross-checking these results with other distance-measuring stars, such as carbon-rich stars and bright red giants, returned a value of 72.6 km/s/Mpc, making it nearly identical to Hubble’s original measurement.

What might have caused the peculiar mismatch is unclear (“I wish I knew,” Riess told Live Science). But speculation is rife among astronomers.

One possibility is that “there is something missing from our understanding of the early universe, such as a new component of matter — primordial dark energy [the mysterious phenomenon that drives cosmic expansion] — that gave the universe unexpected speeds after the Big Bang,” Marc Kamionkowski, a cosmologist at Johns Hopkins University who helped calculate the Hubble constant and who was not involved in the study, said in a statement. “And there are other ideas, such as strange dark matter properties, exotic particles, changing electron masses, or primordial magnetic fields that might be at work. Theorists have leeway to be very creative.”